Big game reality – bluefin tuna

Big game fishing in Britain and Ireland is no longer a dream, writes the Angling Trust’s Martin Salter…

Issue 26 (Jan-Feb 2019) Martin Salter

I dread to think how much of my hard-earned wages I’ve spent travelling the globe in search of the type of reel-screaming, white knuckle action that only big game fishing can provide. Since 2010, when I retired from the House of Commons ‘to spend more time with my fish’, I’ve battled with blue marlin and yellow-tailed kingfish in Australia, sailfish in Kenya, giant trevally in the Seychelles, mahseer in India and golden dorado in Argentina. I’d return to any of these wonderful places again in a heartbeat if time and money allowed. But perhaps those of us who still yearn for the adrenaline filled, and sometimes back breaking, action that these iconic sportfish can deliver might now be able to enjoy our ‘fix’ without even leaving the waters of Britain or Ireland. This is because, contrary to all expectations, and after an interlude of more than 60 years, the bluefin tuna are back.

We have bluefin

As many Off the Scale readers will know, since 2016 giant Atlantic bluefin tuna, including fish well over 700 pounds, have been spotted and caught in Cornwall, in the Celtic Deeps off West Wales, throughout the Western Isles of Scotland and off North West Ireland .

At the Angling Trust we believe that the renewed presence of the bluefin in British waters presents a fantastic opportunity for the UK to “set a new benchmark in the sustainable, economically optimal management of this valuable, vulnerable species.” We have teamed up with our friends in the campaign group ‘Bluefin Tuna UK’ and supportive MPs in the House of Commons to launch a campaign for a live-release recreational fishery that could help many deprived coastal communities in the UK to reinvent themselves as world-class bluefin tuna angling destinations attracting overseas visitors, supporting much needed jobs and businesses in the process. We reminded our politicians that a substantial bluefin tuna live-release fishery already exists in Canada, where studies show that its economic value of is six times per tonne of a traditional commercial fishery.

We’ve made a campaign video which you can find here

Tunny Club

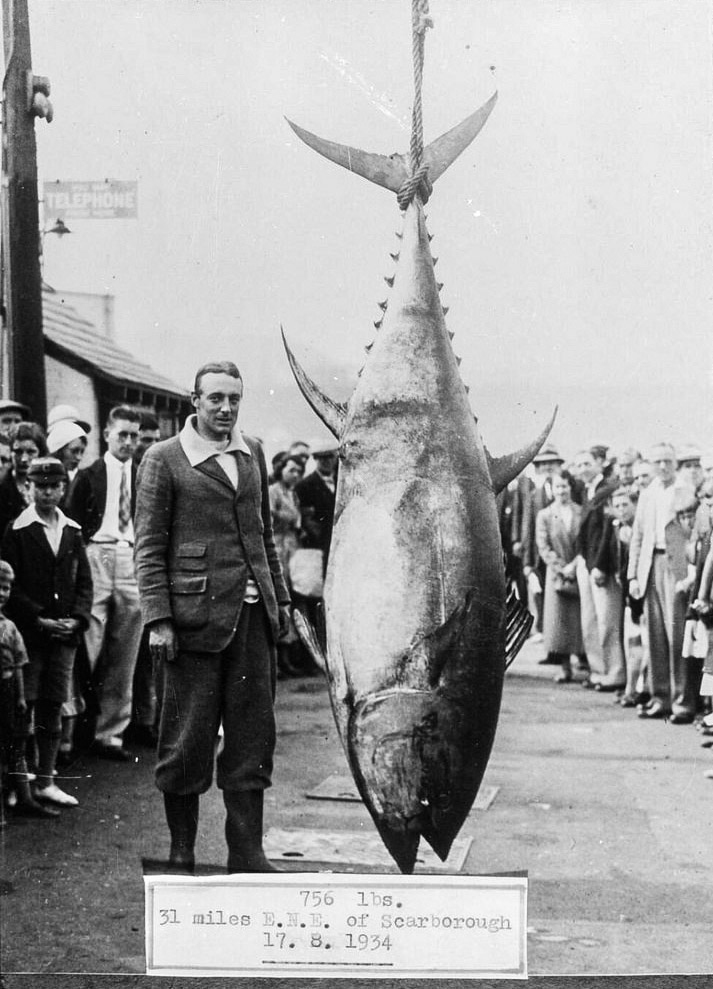

Until the 1950s the UK had a thriving and high-value recreational bluefin tuna fishery operating mainly out of the East coast town of Scarborough, under the auspices of the British Tunny Club (as bluefin were then called). The premises are still a local landmark although now operate as a restaurant. The story of the British tuna sports fishery is inevitably bound up in tales of daring by the British aristocracy and the super wealthy. Tuna fishing was far too grand, and expensive, to be undertaken by us mere mortals. A quick glance through the 1934 Hardy Angler’s Guide (pictured xxx) demonstrates how popular big game fishing had become and the bizarre methods that were deployed to land these giant fish from small rowing boats. I particularly liked this piece of advice:

“Always have a rope tied securely around your waist and attached to the boat before commencing to fish and ensure that your boatman has an open knife to cut your line if necessary.”

Clearly this was no sport for wimps!

Further accounts indicate that;

“Big-game fishing effectively started in 1930 when Lorenzo “Lawrie” Mitchell–Henry, when fifty miles offshore, landed the first tunny caught on rod and line weighing 560 pounds (250 kg). After a poor season in 1931, the following year saw Harold Hardy of Cloughton Hall battling with a tunny about 16 feet long for over seven hours before his line snapped. Also on board the trawler ‘Dick Whittington’ were four visitors who described the struggle as “the greatest fight they had ever seen in their lives”. Mrs. Sparrow caught a fish of 469 pounds (212.7 kg).

Each season up until 1939 saw fish of over 700 pounds (320 kg) being caught and the size of the specimens drew vast crowds. The town of Scarborough was transformed into a resort for the wealthy. Magazines published many sensational stories covering the personalities and the yachts that sailed to Scarborough. There were Lady Broughton, the African big-game hunter, who slept in a tent on the deck of her yacht; Colonel Sir Edward Peel of the wealthy aristocratic Peel family with his large Sudanese-crewed steam yacht St. George; Lord Astor, the newspaper proprietor; Charles Laughton, the actor; Tommy Sopwith, who challenged for the America’s Cup in 1934 and 1937; Lord Crathorne, later Chairman of the Conservative Party; and Lord Moyne of the Guinness family, later assassinated in Egypt.”

All good things come to an end and commercial overfishing of both tuna and herring (their prey) saw stocks collapse, forcing big game anglers to spend a small fortune pursuing these magnificent fish overseas rather than supporting the tourist economy back in Britain.

Recovery

The North Sea tuna are yet to return and globally bluefin stocks took a further nosedive some 20 years ago prompting the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna (ICCAT) to finally begin a stock recovery programme in 2007 which has seen numbers recover sharply from the previously low levels. ICCAT has now ruled that it is safe to increase the global quota from a low point of 12,000 tonnes to 38,350 by 2020. The European Union is a member of ICCAT and has 16,000 tonne quota for its Member States – all but 1-2% of which is allocated to commercial interests – predominantly in Spain, Italy and France. Sadly, the UK, in common with Ireland, Denmark and Sweden, currently has no share of this EU quota and is therefore unable to fish for bluefin either commercially or recreationally. But, of course, anglers being anglers are always going to go fishing and can’t determine which species will take a lure or livebait. Over the last three years plenty of fish up to 320kg have been hooked ‘accidentally’, and released, by those fishing for sharks.

Brexit opportunity

Although personally I’m no fan of Brexit, it is the case that once Britain leaves the EU the UK government would be free to apply to ICCAT for part of the ‘reserve’ quota held for new ‘artisanal’ fishery opportunities. As well as the huge economic and employment benefits, this new UK fishery could contribute significantly to existing science-based research programmes aimed at increasing our knowledge of this iconic and highly migratory game fish. That said, it’s not going to be easy to persuade our ministers to let us deliberately target a fish that was, until quite recently, considered endangered and which has only just reappeared in our waters.

As well as the now obligatory campaign photo-calls, we have been successful in having the issue raised in Parliament by politicians from all sides and have meetings scheduled with our Fisheries Minister George Eustice to press our case for the introduction of a licensed fishery for recreational anglers, which would control the number of vessels deliberately targeting tuna along with a mandatory reporting and monitoring system.

Our proposal

We are proposing that, upon exiting from the EU, the UK applies for Sovereign Member status of ICCAT. With that membership, the UK then requests a small, 20 tonne quota, which could likely come from existing ICCAT reserves thereby avoiding any tricky negotiations to take a share of existing quotas held by other countries. (Should Brexit not proceed we could still approach our EU partners for a quota share and this is something that Ireland should also be considering). The UK would then be able to authorise a recreational fishery, applying that quota as a ‘mortality allowance’ against a live-release fishery.

Live-release fisheries for Atlantic bluefin operate on the premise that a very small percentage of fish will suffer mortality during the capture and release process. Several independent studies have shown that in well-regulated fisheries, such as we are proposing, this mortality is below 5%. In fact, Canada operates their fishery on the assumption of a 3.6% mortality rate.

Based upon the tonnage of the quota, the average size of fish anticipated and the mortality rate applied, a number of permitted captures, or ‘hookups’ can be determined. We would favour controls on the tackle used to help ensure the best fish welfare conditions in order to limit any mortality.

At the heart of our proposal is a parallel research programme designed to provide significant information of value on this valuable, vulnerable species. Various forms of tagging, DNA sampling and recording could all be incorporated into the rod and line fishery, some operated by charter skippers, and more complex operations by authorized scientific teams. It is likely that NGO and/or private sector funding could be mobilised for such operations, as we have seen in the part-funding of the 2017 Swedish/Danish tuna tagging program.

We believe that our proposal and the accompanying rules should be adopted at the earliest opportunity that facilitates a fishery with the characteristics outlined. This would be one of the most highly regulated, scientifically collaborative fisheries for any species on the planet.

Not really asking for much

It’s not as if we are going to be asking for anything revolutionary as there are already tagging programmes, supported by World Wildlife Fund (WWF) no less, taking place across Europe using recreational angling to gather much-needed scientific data to help understand the stock better. The authorised involvement of committed and conservation minded anglers in the fishery would not only add significantly to our knowledge of these tremendous fish but would guard against moves to reinstate unsustainable commercial harvesting and the inevitable illegal fishing that would occur if no one was looking out for the stocks.

There’s a long way to go yet but perhaps one day we might hold the ‘Tuna Home Nations Festival’ with teams from Ireland, England, Wales and Scotland competing to tag and release the largest bluefin. Now there’s a thought…

For more information on the campaign please go to www.anglingtrust.net/BluefinTuna

Martin Salter